Scott Gates as Director of the Centre for the Study of Civil War (CSCW) in 2009. Photo: Marit Moe-Pryce / PRIO

Scott Gates, interviewed by Nils Petter Gleditsch

‘Strong critical theory doesn’t play a big role in peace science anymore, or even in peace studies’, states American political scientist Scott Gates in this conversation with his long-term collaborator Nils Petter Gleditsch. Scott calls for more and better recording of data disaggregated in time and space; more work that takes advantage of quasi-experimental designs and other methods through which we can better ascertain causal inference; and further use of data from social media to better appreciate such phenomena as the relationship between social media use and protest activities.

Nils Petter Gleditsch: I am Nils Petter Gleditsch, and I am going to interview the American political scientist Scott Gates, who has been my colleague at PRIO and NTNU for many years. Between 2003 and 2012, Scott was the head of PRIO’s Center of Excellence, the Center for the Study of Civil War (CSCW). We are going to talk about that, and about the rest of his life. We are going to speak in Scott’s favorite language, which is English.

Let’s start with a little bit about your family background.

Scott Gates: I am the eldest of four siblings. My parents, and especially my mother, are very engaged in issues of peace and conflict. I was a kid during the Vietnam protests. I was 10 years old in 1968 when first Martin Luther King and then Bobby Kennedy were killed. I well remember those events, especially because my mother forbade us to play with guns. We were not even allowed to own them, birthday gifts of toy guns included. Nonetheless, we still played with sticks and made them into guns. On the day that Martin Luther King was assassinated, my mother intervened and laid down the law against sticks as pretend guns: ‘On this day of all days, you will not play with guns.’ Despite how much you read about the proliferation of guns in the US, that sort of parental restraint was not completely unusual in our neighborhood.

We are going to talk later about how you ended up in Norway. But you come from the Midwest, which of course had strong Scandinavian immigration. Was there anything Scandinavian at all in your childhood and youth?

Not by family. My mother’s family is from Winnipeg and my father’s from South Dakota. My ethnic background is mostly English and Scottish and not Scandinavian. But growing up in Minnesota, you can’t avoid becoming familiar with Scandinavian culture. When you have friends named Mikkelsen, Sandberg, and Strom, you get to know things like lutefisk and Christmas celebrated on Christmas Eve rather than Christmas Day.

On the day that Martin Luther King was assassinated, my mother intervened and laid down the law against sticks as pretend guns: ‘On this day of all days, you will not play with guns.’

What about politics?

We had Karl Rolvaag, of course, who was Governor of Minnesota in the 1960s for the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party (DFL). Orville Freeman, Farmer-Labor Party in the 30s before the creation of the DFL. Hubert Humphrey was Mayor of Minneapolis, Senator from Minnesota, and Vice President of the US. Later, there was Vice President Walter Mondale, whose name is an anglicization of Mundal. When I was a teenager, Wendell Anderson was the Governor and later Senator. He was featured in the seventies on the cover of Time magazine as governor of the ‘state that works’.

Politics are different now. There has been a big, big, populist transformation, especially in northern Minnesota. The political composition has changed tremendously, although in recent presidential elections there has been a Democratic majority. The so-called Iron Range mining area used to be solidly Democratic, and now it is solidly Trump-land. When I was a kid, rural Minnesota and the cities voted for the Democrats and the suburbs were Republican. But the Republicans at that time were much more moderate, with a business focus. Close to Høyre in Norway: not populist at all, and not super-conservative. This rural-urban bond comes from the Farmer-Labor origins of the Democratic Party in Minnesota. Indeed, it is still called the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party (DFL).

While he was still Mayor of Minneapolis, Hubert Humphrey stood up in the 1948 Democratic National Convention calling for a voting rights act, black rights, and things like that. The Southern Democrats – the Dixiecrats – led by Strom Thurmond walked out of the convention. Now the Dixiecrat wing of the Democratic party has become die-hard Republican and the old-style liberal Republicans have become Democrats.

A Student in the United States

How did you become interested in the social sciences?

I have been fascinated by history and the social sciences since I was a kid. In sixth grade, my teacher gave me a unique compliment: I should become a history professor. Not just a teacher, a professor of history. Then again in high school, I was told that I should think about doing political science. But every time I responded that I wanted to be a scientist. I started at the University of Minnesota, with a science focus, taking mathematics for engineers, chemistry for pre-medical students, and things like that. On the side, I took political science and anthropology. Eventually I discovered that I was far more talented in those fields than in the sciences. So, I changed track and took a double major in those two disciplines.

With your science background you have presumably had a big advantage relative to many other social scientists in terms of methods, theory building and so on?

That’s probably true. In my honors thesis in political science, I did a quantitative analysis of the patterns of foreign aid. 15 years later, David Dollar in the World Bank published a similar analysis, which got wide attention. I never tried to publish. But I remember that during the oral exam they asked me if I had taken any stats classes. In fact, I had never taken any, but I had enough math to be able to pick up a book and figure out how to run regression analyses. Not to brag, but it was a tremendous advantage. When I started grad school and we had study groups, I had a much greater math background in my cohort than the others.

Then you went to the University of Michigan for graduate studies?

Yes. I actually had two separate lives at Michigan. In 1980, I graduated from Minnesota on schedule with that double major plus a minor in economics. I was accepted for graduate studies at the University of Michigan as well as at Washington University in St. Louis. That was an up-and-coming department at the time. They had lots of money; they flew me down with some others to St. Louis to convince me to go there. I was going to work with Kenneth Shepsle, who was a very big congressional scholar. He wanted me to do game theory and study the US Congress. Shepsle, as it turned out, would have left for Harvard as soon I was in the middle of my dissertation. So, I am not sure if that would have been a great move for me.

The alternative was to go to Michigan and be in a slightly riskier position without a guaranteed scholarship but have the possibility of working for J David Singer at the Correlates of War (COW) project. A choice between studying international conflict or staying with the US Congress. I couldn’t imagine spending the rest of my life studying only Congress, as interested as I am in American politics.

Tell us a little more about the Correlates of War project – which has been important for PRIO, too, in several ways. Singer founded it while he was in Oslo on sabbatical in 1963–64.

Oh, really? I didn’t know that. Michigan had been a hotbed for studying conflict from a multidisciplinary perspective. The COW project was based at the Mental Health Research Institute, located quite far from the Political Science Department, the Institute for Social Research, and the Institute for Public Policy Studies. Singer had over twenty graduate students working for him. He was extremely well funded, and it was a bit like a factory. Some were analysts. Others only gathered data. People had specific roles and a place on the factory assembly line. I was very fortunate because I came from the outside and was funded by the department rather than by the project.

Singer had received a letter from Rudy Rummel, which criticized an article that Singer and his colleague Mel Small, a historian, had written for the Jerusalem Journal of International Relations critiquing the idea of a democratic peace. Rummel had dug up work on the democratic peace by a criminologist named Dean Babst. Rummel tried to build upon Babst’s work by looking at all dyads at war to see whether two democracies ever formed such a dyad. Singer wanted to pursue this further and put me in charge of that project. I was the only person out of the twenty who were working at the Correlates of War project who did everything: I read the literature, I developed theory, I worked out the research design, I did the data analysis. At a meeting at the Correlates of War project, Zeev Maoz suggested that I look for measures of regime type in Ted Gurr’s Polity dataset, published in 1974.

Rummel didn’t publish his first article on democratic peace until 1983, I think.

That’s right. It was this article that Singer had given to me. Singer was supposed to be a reviewer, but he gave it to me. In my comments, I noted that there were some aspects of the article which were impossible to replicate because not enough detail was given. Remember, I was just a first-year graduate student. I wrote something to the effect that: ‘Given this lack of information, I can’t replicate the results.’ Singer took that sentence and went on at length about how it couldn’t be replicated, which went well beyond what I had meant. I had just noted that more information was needed to replicate the results.

This disagreement occasioned my first introduction to Singer’s temper tantrums. I hadn’t realized the extent to which he was depending on a first-year graduate student for his professional work. In any case, Rummel got a revise and resubmit and his article was eventually published in Journal of Conflict Resolution. In the meantime, I worked on my master’s thesis on the democratic peace. I presented a paper at the spring meeting of the Midwestern Political Science Association in Chicago. This is kind of the number two political science convention in the US, after the American Political Science annual meeting. It was unusual for grad students from the University of Michigan to present at professional meetings. I remember riding an elevator in the political science building at Haven Hall with one of the junior professors who scoffed that I had the audacity to be presenting a paper as a second-year grad student! But I got really good comments at the meeting. Singer knew about this and had supported me doing it. Then, when we met, he said the paper required some editing, and that how much editing he did would determine whether he was the sole author, or co-author. I responded that I had done everything: I had written every word, done all the statistical analysis. Everything! And I could see where that was going, that I would get zero credit for it. I commented that I thought it was too high a price to pay for editing. Singer exploded. He stood up in full red-faced rage. He started the meeting with me being wonderful, and such a bright prospect, and he ended by saying that I was an absolute dunderhead. That there were serious doubts about my ability to finish or do anything.

I left the room not giving him the paper, or the authority for it. I had a long conversation about my predicament with John Jackson, who was in public policy and statistically oriented. I decided to leave Michigan, but on Jackson’s advice, I took a leave of absence. In my mind, I was quitting political science and going back to the University of Minnesota in applied economics. I would switch from conflict to development. In economics, at that time, it would be very difficult to study peace and conflict. Todd Sandler was doing it, but he had a job at the University of Wyoming at that time.

[Singer] said the paper required some editing, and that how much editing he did would determine whether he was the sole author, or co-author. I responded that I had done everything: I had written every word, done all the statistical analysis. Everything! […] I commented that I thought it was too high a price to pay for editing. Singer exploded. He stood up in full red-faced rage.

There was Kenneth Boulding, of course, but he had a very interdisciplinary approach.

He did. Anyway, I joked that my future would be at Montana State and even though the town of Bozeman might be a nice place to live, that was not what I aspired to do. Maybe that was kind of arrogant. But that’s where I was. I just didn’t want to work as hard as I would have to do in economics and then have to pay a high cost.

I had big psychological issues with the Singer controversy. He contacted me later and asked on behalf of Zeev Maoz for the data. I had not touched my master’s thesis or that Midwest paper. I gave all my data to Zeev Maoz. After all, he was the one who had helped me with the paper when I presented it at the COW seminar.

You still have a copy of your master’s thesis? I’d like to see it!

I should probably scan it and put it up on the web.

Please do!

Anyway, Zeev got my data and my paper and he got an American Political Science Review (APSR) article out of the topic. I do remember Rudy Rummel thanking me in a footnote in the 1983 Journal of Conflict Resolution article. Somebody said: ‘Well, you got more thanks from Rudy Rummel than you ever did from J David Singer’.

In any case, I left for Minnesota and got another master’s degree in applied economics. I worked with a guy named Vernon Ruttan, who worked on technology transfer and agricultural development. My Master of Science (MS) thesis was entirely a formal game theoretic model. After obtaining my MS in economics, I decided that political science was much more interesting for me than economics. I went back to Michigan, but rather than Singer I worked with Harold Jacobson, who specialized in international organizations, and with John Chamberlain, who had worked on collective action problems. He had a doctorate from Stanford, where Robert Wilson, who won the Nobel Prize in economics this year, served as his dissertation advisor.

My doctoral dissertation was on aid conditionality. I went to Pakistan to compare World Bank and US Agency for International Development (USAID) conditionality. I developed a theoretical model that could be generalized to bureaucracy. A year after defending my doctoral dissertation, I was sharing a hotel room with John Brehm, a friend from graduate school at Michigan. We started talking about bureaucratic politics and decided to work together. I from the rational choice perspective and he from the psychological. Over time, the psychological perspective fell away, and we combined my games with statistical analysis. With John Brehm, I co-authored several articles and two books on bureaucracy. Brehm is an Americanist and an expert on public opinion. John and I won the Herbert Simon award for the scientific study of bureaucracy. I am probably the only peace scientist to have won that award.

John and I also worked on police brutality, and right now we are rekindling some of this work in the light of what has been going on in the US. We are going to start looking again at the US police and the excessive use of force. I have always wanted to combine my two lives and I think the police brutality work nicely combines peace science and the study of bureaucracy. Our first book featured the street-level bureaucrat. The policeman and the social worker. The bureaucrats on the street, so to speak, interacting directly with the citizenry. Street-level bureaucrats possess considerable decision-making discretion and agency. We examine how they spend their time across tasks. The book is entitled, Working, Shirking, and Sabotage. Working constitutes positive expenditure of time to produce public policy. Shirking, which stems from laziness or political opposition to a given policy, involves no work effort. Sabotage involves work effort used to undercut the implementation of policy.

We also examined police brutality. We took two different datasets (one of which had been collected by Elinor Ostrom, the Nobel prize winner) on the nature of police-citizen interactions, including police brutality. We were able to merge these observational data with personal psychological data, matching on the officer. We found that those officers with a psychological proclivity for violence were far more likely to engage in police brutality. They also served to ‘infect’ those around them. Officers who normally did not engage in violent altercations with citizens were much more likely to be brutal when on duty with a violent officer.

We found that those officers with a psychological proclivity for violence were far more likely to engage in police brutality. They also served to ‘infect’ those around them.

Your work on bureaucracy was a spin off from your development studies?

Yes. The Pakistan office of the USAID was the agency’s biggest operation, mainly because the Soviet Union was in Afghanistan. A massive amount of development aid was channeled to Pakistan and it was handled by a huge staff. At the time, the World Bank also had one of its largest contingents in Pakistan. I was able to compare the two. I found that the local staff developed close ties with their fellow bureaucrats on the Pakistani side and became estranged from the Washington bureaucrats. They actually had more in common, so the USAID staff engaged in policies closer to that of the Pakistanis. This is part of my theory about bureaucratic sabotage. What I witnessed in Pakistan, in particular from lower-level bureaucrats, was that at the final aspects of implementing policy they actively spent their time undercutting the policies to make sure that they were never put in place. Ever. They effectively used their time to sabotage the policies rather than to effectively bring them forward. Out of that came my book with Brehm about working, shirking, and sabotage in bureaucracies.

What was your relationship to the Correlates of War (COW) project once you returned to Michigan?

I really had nothing to do with it. I heard about it, of course. Among other things, I was a good friend of Paul Diehl, who had Singer as his advisor but never worked for COW. As Paul said, he never milked the COW, and that allowed him to have much more freedom and leeway in how he wanted to do his work.

So, you finished your dissertation, and then your first job was at Michigan State?

After my field work in Pakistan, I returned to Ann Arbor for half a year. That spring, the Department of Political Science at Michigan State University called me. They needed someone to take over Jim Morrow’s courses, since Jim had been hired by the University of Michigan. Jim’s courses at Michigan State were statistics for graduate students, world politics for undergraduates, and graduate seminars in international politics. I started teaching, although my dissertation was not yet finished. I remember I had a conversation with my father about it. He said it would delay my doctoral dissertation, but it might put a foot in the door for getting a job there. Michigan State is a top research school and has done very well on international rankings. We were also a really young department and an exciting environment.

The one problem was that the department had almost no international politics people. I was probably attracting half of the graduate students, and they did very well. In the US, there is a distinction between R1 schools, i.e. research schools, and non-research universities. Among all the Michigan State graduate students in political science 1995–2005 – and mind you I left Michigan State in 2002 – I had over half of all the R1 placements. And I was only one out of 32 faculty members. That was partly because they would never hire an international relations guy. Gretchen Hower, a student of Dina Zinnes and the smartest person in our department, was there for a while, but she left academia. In my final years, they hired Bill Reed, who was super smart and a fantastic colleague. Reed is now at the University of Maryland.

These things never follow a normal distribution, whether that is students, publications, or citations.

International relations was a popular topic. I was single and able to dedicate tons of time and energy to my teaching. But you know the legacy: Sara Mitchell at the University of Iowa was one of my students, Brandon Prince was another, Mark Souva at Florida State.

We are getting close to your move to Norway. You were recruited first into a temporary position at NTNU, or the University of Trondheim as it was called at the time. How did that come about?

Moving to Norway

A housemate in Ann Arbor and an extremely good friend of mine was a Norwegian-American named Richard Matland. He was an undergraduate from the University of Wisconsin. There is a friendly rivalry between Minnesota and Wisconsin, and at our first meeting we started arguing about Minnesota vs. Wisconsin college sports. We met as graduate students at Michigan.

I remember Rick speaking rather quaint Norwegian …

Someone told me he spoke the language of his grandmother, who was from a tiny little island in Western Norway. Although he was completely fluent in Norwegian, all his pause words were English. He would rattle off in Norwegian and then he would go ‘um ahh, anyways’. In any case, Rick used any opportunity he had to come back to Norway. His wife was Norwegian, and he wanted his daughters to be fluent in Norwegian as well. He had spent a year at the University of Trondheim with Ola Listhaug, whom I knew from a party at Michigan when he was a visiting scholar there in 1982 or thereabouts. Ola knew Rick quite well.

One day in late 1993, Ola called me in Michigan and said, ‘I have an offer you can’t refuse: You teach one class, give a lecture on the American presidential election and you can finish your work to get tenure – and then you come back for your tenure year’. My department at Michigan State was in a budget bind at the time, so they were happy to see me go and hire a graduate student to teach my classes. I went to Trondheim after the Lillehammer Winter Olympics, in the summer of 1994. The glow from the Olympics was still there. I had a fantastically productive year. I finished two books and two articles in that year, so I had more than enough for tenure when I returned to Michigan State. I even took Norwegian classes, which is kind of funny in retrospect because I was only going to be here for one year.

From left: Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, Nils Petter Gleditsch and Scott Gates on Mount Hornindalsrokken, July 1999. Photo: Private archives

For the uninitiated reader, we are talking about the person who founded political science in Trondheim.

Ola Listhaug was a genius when it came to running the Department of Sociology and Political Science. He knew that he couldn’t let the new political science section grow too quickly, or you could end up filling it with people you wished you had never hired. So, he hired strategically, especially PhDs from the US. If they stayed, as did Torbjørn Knutsen, Jonathan Moses, Jennifer Bailey, and Indra de Soysa, that was fine. But for many others, such as me, he anticipated that we would not stay in Norway. We kept some seats warm, which he could use to recruit others in due course. He hired Han Dorussen, who stayed longer than I did but eventually went to the University of Essex. But I kept coming back.

Now we’re talking about the early 1990s?

I got tenure once I returned to Michigan State, and after tenure you are up for sabbatical. I had thought that I was going to get an invitation to the University of California San Diego, but that went to Hanne Marte Narud instead. So, then I elected to go back to Norway. This time I had to work a little bit more or, as Ola said, I had to sing for my supper. So, I came back to what was then called Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet (NTNU), and I taught courses. This was when the two of us first met. I remember that I presented a paper on the democratic peace with Sara Mitchell at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association. You came up to me afterwards and expressed an interest in cooperating. That summer, I remember I came down from Trondheim to visit PRIO, and …

Getting to Know PRIO and Love

Of course, I had been teaching in Trondheim for a couple of years then. But I was in an adjunct position, so I only came there for the day and taught my course and talked to my students and left again. So, I didn’t know that many …

You probably knew more students than faculty.

Yes. There was a lot of interest in international relations, a little bit like what happened to you at Michigan State. Suddenly I found all these students coming to my class and signing up for theses.

To break off from the chronology for a minute. At the time I assume you had heard about Johan Galtung, PRIO’s founder?

Oh, definitely. We talked about him in graduate school.

Had you read any of his work?

I remember his sanctions paper on Rhodesia, which I thought very highly of. I was more critical of his work on positive peace. The idea is brilliant, but it’s a little bit too much of anything good is peace. I was rather critical of that, and I still am. But certainly, those two pieces I remember quite well.

Well, to return to my association with PRIO, I would not be here if it wasn’t for you. I kept coming down to PRIO from Trondheim. Because we did join forces on the democratic peace and wrote grant proposals for the Research Council of Norway and for the National Science Foundation in the US. In fact, for a while I was spending more time here in Oslo even though I was supposedly teaching in Trondheim for the semester. Then you took some time off to go to Uppsala to teach. You needed somebody to take over your editorial duties at Journal of Peace Research (JPR), and I was very eager to do this.

I remember saying to myself when you made the offer, that ‘this is my last time in Norway’. Famous last words! I thought that it would be interesting as well as good for my career. I really liked the idea of serving as an editor for a while. And once that was done, I would get serious and start thinking about getting married and what not. I was over 40 years old. Time to get serious in my head.

Scott with his family outside a Buddhist temple on Jeju Island, South Korea, October 2010. Photo: Private archives

At the time, did you ever consider the possibility that you might become a permanent resident in Norway?

No way! There was zero interest. But then you invited me to a party, and you put me at a table with Louise Harnby from Sage and Ingeborg Haavardsson, PRIO’s communications director. According to Ingeborg, she was interested in me, but I did not have any interest in her at all. When Ingeborg returned from a sailing cruise in Scotland, I invited her out to the Jazz festival and then we became romantic. I was living in a flat in Oscars gate at the time. There were two entrances. I would normally use the front entrance but for some reason I took Ingeborg to my apartment through the back entrance. And one day just by chance I saw tucked into the doorframe of the back entrance a little turquoise envelope with ‘Scott’ on it. I was really surprised to find a very tender romantic note from Ingeborg about how wonderful it was to have met me and everything else. But basically, it all started at your party.

It was a dinner during the editorial committee meeting of JPR. I am glad it worked out, even though I can no longer remember if my seating plan was deliberate … In any case, I have said many times that Americans will almost never give up a tenured position to take a job in Norway. Americans who work in Norwegian universities usually have come here before tenure became an issue. Or because they were denied tenure, frequently for the wrong reasons because of animosity in the department and that sort of thing.

Of course, the overwhelming majority come because they have found a Norwegian partner. Many Norwegian women in particular are strong enough to keep their men here, as opposed to moving to the US. You fit the pattern for the second point, but not for the first. You did get tenure.

Directing PRIO’s New Center of Excellence

Yes, I did give up tenure in the US and mainly because we got funding for a Center of Excellence. You and I had worked very hard together on an application to the Research Council for funding the Center for the Study of Civil War (CSCW). At the same time, I had also applied to be the Director of PRIO. I didn’t get that job, which in retrospect I am thankful for.

You placed a good number two! Most of our colleagues probably assumed that you were my favorite to get the directorship, whereas in fact, I thought that you would be wasted as Director of PRIO. If you placed number two, you’d be in a stronger position of authority as the Director of the Center. That position was of course situated under the Director of PRIO, but we needed to establish the Center Director’s authority.

Yeah, but the Research Council of Norway gave me considerable authority because they had explicitly said that any Center was to be an autonomous organization within whatever body it was part of.

Did you ever think that getting funding for a Center of Excellence at PRIO was a realistic option?

No, I didn’t. I had also received a job offer from Uppsala University of a chair in the Department of Peace and Conflict Research. But the salary was very low, lower than my Michigan State salary. That was another tough decision and Peter Wallensteen really worked hard on it. But I was not prepared to take a pay cut to live in a more expensive place. So, I turned that down.

But then you also had a new job offer in the US?

I was offered an endowed professorship with really good pay at the University of North Carolina. That was very interesting, and I had been contemplating trying to accept both. To be at PRIO and take the job at North Carolina with a reduced assignment and, after the Center had run its course, to reverse the relationship.

This sounds to me like you would be modeling your lifestyle on Johan Galtung?

Well, Ola Listhaug gave me some personal advice. There are three factors that are going to be affected here. They are your health, your marriage, and your career. You can’t maximize on all three. One or two of them will suffer if you try to do a transatlantic job. Eventually, I decided that the costs were too great and gave up the North Carolina option. At that time, with two young babies and an eight-year-old in the house, it was the best decision by a long shot.

Then, despite your misgivings, the Center application was successful.

I remember on the day we were told, I met you in the reception area of PRIO’s office in Fuglehauggata. You asked if I’d heard anything, and I said no.

I think I also said if you get a call before 10, we’re in. They will call the successful ones first…

Yes, this was about 09:15 and I went upstairs to my office. As I crossed the threshold, the phone rang. And there they were! The Research Council. The irony is that I so little expected it that four days earlier Ingeborg and I had bought a house in East Lansing.

We did get a bit worried when we heard that you had an offer of an endowed faculty position at North Carolina. Fortunately, Ola Listhaug arranged for you to get a permanent full-time professorship at NTNU with 80% indefinite leave. This was quite an unusual arrangement. It was the kind of thing that Ola Listhaug could manage and few others.

Of course, I already had a 20% adjunct position at NTNU, a Professor II job in organization theory. That made it much easier for him to get me a 100% position with 80% leave, because the cost was the same. Ola really wanted this to work and he was able to get the university to approve the arrangement.

Well, it was a bonus for NTNU to be associated with another Center of Excellence in addition to their own three Centers.

Yes, and Ola Listhaug was already a working group leader at the Center as well.

I told [Jon Elster] that all his life he had tried to understand why people cooperate when you would expect them not to. So why not look at conflict, too? Have you thought about destructive conflict relationships like feuds and war? They do not seem to make sense from a rational perspective and yet perhaps they can be explained through rational choice theories.

From top left: Kalle Moene, Kaare Strøm, Jon Elster, Pavel Baev, Nils Petter Gleditsch, Scott Gates and Ola Listhaug. Working group leaders for CSCW, January 2003. Photo: PRIO

Do you want to say a few more words about recruiting the working group leaders for the Center?

I was very keen on trying to entice people who were not conflict people. To bring people from other fields to provide new insights into conflict research. Like Ola Listhaug, who was a public opinion specialist. And, of course, Jon Elster.

Jon was associated with a project at the Center for Advanced Studies in the Norwegian Academy of Science. I went down to Drammensveien and had a meeting with Jon. I had never met him before. I thought the world of him. I had read his books, and I remember how phenomenally well he writes. As a graduate student, I had heard that English was his third language. I told him that. Then he confessed that no, his French was not as good as his English. Jon doesn’t suffer problems with his ego, but he still had enough humility to say that.

In any case, I told him that all his life he had tried to understand why people cooperate when you would expect them not to. So why not look at conflict, too? Have you thought about destructive conflict relationships like feuds and war? They do not seem to make sense from a rational perspective and yet perhaps they can be explained through rational choice theories. I think I hooked him with that conversation. Jon became fully engaged and brought some phenomenal intellectuals to the Center.

Such as Jim Fearon and Diego Gambetta …

Exactly, and Jim Robinson. And the interesting thing is that some of these guys he was so hard on. Jon was scathing in his critiques of Jim Robinson. But they would still come back. Jon also blended really well with Kalle Moene and his group on economic factors in civil war.

You may remember that Jon first declined because he was a part of a planned Center of Excellence application from the Institute for Social Research. We called Jon in Paris from my office just a day or two before the deadline, just to make sure, and it turned out that the application from the Institute of Social Research had imploded.

That’s right. Perhaps my hook wasn’t as successful as I thought.

He was interested, but he felt he already had another commitment.

That’s right. He had said, ‘I would rather be with you, but …’. I remember that now.

Another person you recruited from the start was Kaare Strøm. As I recall, that was a part of our strategy to bring into the application some prominent Norwegian expats. Social scientists of Norwegian origin who could not be brought back to Norway full time, but who were interested in having a connection to Norwegian academic life. A part-time position as a working group leader was in many ways ideal.

And Kaare also fit the pattern as an expert in other areas, such as institutions and governance, who hadn’t previously worked on conflict. Of course, subsequently he has, particularly on power sharing and peace.

How would you assess the CSCW overall?

Nils Petter Gleditsch and Scott Gates at the CSCW launch at Vitenskapsakademiet, 6 January 2003. Photo: Private archives

I think, as a whole, it was an unmitigated success. We had a profound impact on the study of civil war. We still do, especially on the geography of conflict. The PRIO-Grid, using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), came out of the Center and will have a lasting impact.

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data project (ACLED) was also developed at the Center. We were already so committed to working with UCDP (the Uppsala Conflict Data Program), so I told Clionadh Raleigh that she could go forward with ACLED and we would make no claims on the data. ACLED has been amazingly successful. It is used regularly by The Economist and by the World Bank. And Clionadh has recruited a group of permanent staff at the University of Sussex that keep it going.

The stamp that we helped to put on the conflict data from UCDP is also indelible. Backdating the armed conflict dataset to 1946 and making it more easily available to other researchers was a phenomenal achievement.

I think, as a whole, [CSCW] was an unmitigated success. We had a profound impact on the study of civil war. We still do, especially on the geography of conflict.

Doubting (or Dissecting?) the Democratic Peace

The democratic peace was, of course, an important element of the Center’s research profile. If we go back to the first applications we wrote to the US National Science Foundation and the Research Council of Norway, you posed as an opponent of the democratic peace and we wrote the application as ‘an enthusiast meets a skeptic’. That turned out to be quite a successful formula. But you probably stretched the skepticism a little bit?

Well, I was not a true believer. I was critical in some ways. I had co-authored a critical article with Torbjørn Knutsen and Jonathan Moses in Journal of Peace Research. In that group, I was the most favorable towards the democratic peace. My main point was that I wanted more real theory. The democratic peace was a result in search of a theory.

Then came our 2001 APSR article with Håvard Hegre and Tanja Ellingsen …

Which is probably your most frequently cited article …

What about my 1997 book with John Brehm?

That’s your most-cited book, but still less cited than the APSR article.

In any case, we framed that article around the civil democratic peace. It was successful at the time and still gets cited frequently. But less frequently than its contemporaries, Fearon & Laitin (2003) and Collier & Hoeffler (2004). Those two were framed as theories of civil war. We really did have a theory of civil war too, but we didn’t frame it that way.

Well of course both those two articles went for an opportunity theory of civil war, which at the time seemed like a novel approach, even though it was part of Ted Gurr’s old formula in Why Men Rebel (1970) or the Siverson-Starr ‘opportunity and grievance’ model (1990).

Our model was more grievance oriented. Actually, ours was both. Both grievance and opportunity are embedded in the parabolic relationship. In autocracies, there is little opportunity to rebel, while in democracies there is little grievance. In semi-democracies, the product of opportunity and grievance is the highest, so they are the most prone to civil war. If we had framed that as the key point of the article, perhaps we might have had even more citations.

Right.

The original Center grant was for a five-year period. And then it could be renewed for another five years. In fact, I think that all the Centers from the first round were renewed. You seemed quite annoyed at that, after we had put so much hard work into the second-round application.

We were rated, or so I was told by one of the Research Council Administrators of the Centers of Excellence, as number two in an overall assessment, after the geohazards group. That was quite flattering. Bergen had two Centers which were originally recommended for non-renewal. In one of them there had been a lot of internal squabbling and arguing. It would have been very easy for the Research Council to have just said ‘we are sorry …’, but they still let both through after the university lobbied. I was really irritated because I had put a lot of time, sweat, and anxiety into that renewal process. And then it didn’t really seem to matter.

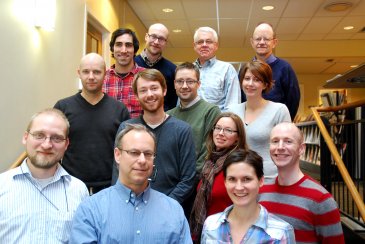

CSCW Staff, 2011. Photo: PRIO

If I were to say that, in designing the second period, you were a little bit too soft in keeping on all the working group leaders?

No, I went through three leaders in one working group and I eliminated myself. One thing that I had done wrong in the first round was that I was a working group leader as well as the Director. I also took much more control of the budget and created incentives for the leaders. If they got an outside grant, they would double the allocation to their working group. If they didn’t get any additional funding, they would get less every year until there was just a pittance in 2012. Most of the working group leaders responded to this incentive, and we got lots of outside money. So, we weren’t relying entirely on the Research Council. I didn’t see a reason to just get rid of a working group leader just to get rid of somebody. You had to have good reasons for it.

Of course, one general weakness of the Center model as set up by the Research Council was that the host institutions had a big incentive to hire for the Center people who had failed to get outside support.

I refused to do that. And you were very strong in this regard. We both were.

One of the new hires as a working group leader was Jeff Checkel. Jeff was the furthest away from all the other working group leaders intellectually, from an ontological perspective. I believe that Jeff changed more than we did. Jeff became less critical in his critical theory. He didn’t become quantitative, but he became more empirical. And …

… more appreciative of quantitative work?

… and much more open to new methods, and especially mixed methods. Jeff has been very helpful. He is now an associate editor at JPR. That decision was made before I became editor, but I rely on him quite often …

… and of course he has continued to give courses at PRIO.

He and I have taught together. An odd pairing, but it works.

After the Center, did you feel a little bit like an athlete who retires after winning gold medals?

No, quite the opposite. Now I have more time to do my own research rather than administration. One big problem was that I was having big trouble finding funding for my grant applications. In particular, I was annoyed by responses to applications to the Research Council which said that since Gates has already gotten more than enough money from the Research Council, we don’t need to fund this project. You get a good evaluation, and then you are told you can’t get the money.

This is Norwegian egalitarianism striking back, you see. After a period in which excellence was rewarded, which of course was inegalitarian in many ways, the Research Council goes back to its old ways.

Exactly. Just after I received that letter from the Research Council, Jon Hovi called me and said they had an opening in political science at the University of Oslo, and so I said yes, I would apply. And then I took a full-time position at Blindern.

Of course, you like teaching?

Yes, I really enjoy teaching. I was teaching in Trondheim but teaching there is hard on your body.

I know from personal experience …

… because you wake up early, and you’re still working on your lecture in the taxi, and on the plane, and then when you go home in the evening after teaching the entire day, you fall asleep in the taxi, go through security, and fall asleep again on the plane.

Falling asleep in the taxi is a good characteristic, at least you get some rest. I was quite proud of being able to fall asleep in the taxi.

Editing Journals

I must say that PRIO has been very good in maintaining my research relationship on a part-time basis. I have not been kicked out of my office. The entire arrangement with PRIO and the University of Oslo has been ideal. And then last year, I was told that there was a crisis at the Journal of Peace Research when Gudrun Østby wanted to step down as editor. There was a lot of anxiety among others at JPR about who the next editor would be. Then I said, well you know I kind of was interested a long time ago, and no one had thought that I would ever take the job. But as it turned out, I did. It’s a lot of work, but I don’t dislike it.

What’s the number of submissions now? Over 500 per year?

Over 500 in 2019 and still rising. The last article we received is JPR-20-0570. 570 submissions this year, so far. We might pass 600. [614 articles were submitted in 2020].

That is a big increase since my time!

… or that time in 1999 when I took over while you were in Uppsala.

When I became editor in 1983, the first year of my long period as editor, I had to put two of my own articles into the journal in a year because of a lack of submissions. One successful, and the other a total failure. Anyway, were you disappointed when I retired as editor in 2010 and recommended Henrik Urdal rather than you as my successor?

No, because I was still Center Director. It was impossible for you to have pointed to me. I realized that. I didn’t think it was possible for me to do both jobs. The number of submissions wasn’t as high as it is now, but it was growing, and I thought it was going to continue to grow.

Academic journals are now in a bit of flux with the calls for open access, digitization, and so on. How do you see the future of the academic journals? Will we end up without journals and just archives or what?

That is an interesting question … You could have peer-reviewed article archives and special issues where an editor puts together a group of articles. And those special issues might be virtual. There are so many exciting opportunities as we move away from the print medium. Animations and three-dimensional figures are possible with electronic presentation, but not with print. Linking appendices and articles is easier too.

Scott speaking at a seminar for PSYOPS: The Psychology of Political Struggle, 2017. Photo: Ebba Tellander / PRIO

You also edit another journal, International Area Studies Review (IASR). How did that happen?

Michigan State University is one of the prized destinations in the US for Koreans. I think it began because Michigan State is a top agricultural school. The Korean connection seems to date back to the fifties. A lot of scholarships were given for development-related agronomy and things like that. Many Koreans started going there. This led to a more established link between Michigan State and Korea and students from other fields started going there, including political science. So, when I went to Michigan State, we always had several Koreans.

One advantage was that political science at Michigan State was extremely quantitative, even more so than the better-known University of Michigan. Michigan has the reputation, but Michigan State was more advanced in training graduate students. That was good for the Koreans, because they have quite onerous math requirements just to get into the university. So political science offered courses where they could get a good grade with their competence in mathematics. Of course, international politics is more interesting to most Koreans than American government, so I became the supervisor to a lot of them.

They became public administration scholars or specialized in international politics. Back at that time, I was still an international political economy person. I was interested in conflict, but I wasn’t doing research on conflict. My own dissertation was on conditionality and my very first student, Sang-Hwan Lee, wrote on trade politics and trade conflicts. We have stayed in close contact. His university, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (HUFS), had a journal called International Area Studies, edited at their Center for International Area Studies.

In 2010, he approached me to ask if I was willing to serve as the editor of the journal. We had the journal’s name changed to International Area Studies Review and signed a publishing contract with Sage. IASR is now published on the same model as the two PRIO journals, JPR and Security Dialogue. HUFS owns the journal, while Sage offers publication services on a contract basis.

Of course, International Studies Review is a name claimed by a better-known journal published by the International Studies Association, but there is no monopoly on journal names.

Exactly. Their International Studies Review was older than the other one, but I thought the new name was truer to the journal’s mission. Although the international standing of IASR is still limited, it is improving and overall, I think it has gone pretty well. In part as a spin-off from this relationship, I am now organizing a conference on the Korean Peace. A virtual conference due to COVID. I was also brought in on some back-channel stuff that PRIO was part of along with Stein Tønnesson and Pavel Baev, in which we met dignitaries from North Korea. I was even invited to come to Pyongyang, but they did not know that I was American. They thought I was Norwegian. I thought if it came out that I was an American, it could cause trouble for the meeting, so I withdrew, even though it would have been interesting.

Is there any problem being the editor of two journals at the same time?

No, the main problem with IASR is the lack of good submissions. We get well over 100 submissions per year, but most of them pretty poor. I put a lot of effort into promoting scholars from the global south through IASR. But even when good, those articles are hardly ever cited, and this hurts us in terms of impact factors and so on. I am not sure why they are not cited, but it could stem from the authors having no network. The journal unfortunately does not always attract the attention it deserves. Nevertheless, I have been happy to work with Norwegian scholars who do article-based dissertations. The introduction (or the ‘kappe’, in Norwegian) is an overview of literature. Usually, you don’t have an avenue for publishing those things, but we do. Gudrun Østby’s assessment of horizontal inequality is a particularly successful example.

Such articles probably provide good course material.

Precisely, so we do better on metrics of downloads than on citations.

Peer Review and Joint Authorship

I also want to ask you a little about peer review. When we first started systematic outside peer review in JPR in 1983, several people, including people on the editorial committee, asked if we didn’t have to build a base of reviewers first. I said no, we just test people and then we build that base as we go along.

We found that some people were willing to review, and some were not. Surprisingly few were not. But of course, with over 500 articles per year, and three reviewers per article, that is over 1,500 reviews and there is a limit to how many times you can ask the same person.

I try not to ask anybody to review too frequently, even though we have relaxed the policy of not more than one request per year. We also have many more desk rejections, articles declined without review. This might be well over half. We have an editor specifically designated to desk rejection. Then I review his suggestions and I rarely desk reject something that he suggests is okay, but I do send out for review some that he recommends rejecting.

Torbjørn Knutsen once told me that he had taken a course from Henry Kissinger. Kissinger would only read the As, or so claimed one of the teaching assistants. If this was true, the teaching assistants in fact decided who got an A. It would be the same thing with desk rejections unless the editor reviewed them.

That is correct. I also know that the associate editors apply somewhat different standards. Some are kinder than others. If I send out an article that I view as reviewable, but weak, I don’t send it to the kind associate editor. I don’t think that would be fair. If you are not aware of the differences between the associate editors, you could have a kind one giving a go to everything. While a lot of sophisticated work judged by a stricter associate editor would not get through.

One innovation that I really want to push forward with the publishers is to provide animations and other forms of visual displays of data. SAGE has been reluctant, partly, I think, because of the cost and partly because of lack of staff expertise. This would move us towards electronic media, and not print media. Having an ability to promote three-dimensional figures, dynamic graphs which are moving and changing, would be a big breakthrough for JPR. I really think we would be unique among journals.

One of the things that struck me at the most recent editorial committee meeting of JPR was all this discussion about getting a third review where the first two disagree. It struck me afterwards that despite the great value of peer review, there can be too much reliance on the reviewers. There are even stories about journals where if one reviewer says ‘no’ the article gets rejected. Of course, JPR has never practiced that.

No, but American Political Science Review has often done that.

My feeling is that when two reviewers disagree, then it’s the job of the editor to decide.

I live by that standard. I try to get three, but if I don’t get the third, I decide. I am encouraged by finding that, despite reviewer fatigue, there are always young new researchers willing to review articles. Especially as conflict research is becoming more common in economics, there are more and more junior economists who are willing to review. For a lot of the types of articles that we are getting, that has really increased our pool.

I also look for younger scholars when I solicit reviewers for JPR’s Book Notes column. The problem is that as we get older, it may be harder to find these young people.

I use Google Scholar a lot. And some scholars do recommend others, frequently younger colleagues. When I decline a review request from another journal, I try to do that myself when I say ‘no’.

Talking about younger scholars. We talked about your one-time mentor J David Singer and that article about democratic peace where he suggested that you might get to be a co-author. It struck me that Singer co-authored quite a bit in his time, but rarely with graduate students. The same goes for Rudy Rummel, although he generally co-authored less. This is very different from my own experience and from the atmosphere at PRIO today, where grad students and senior scholars co-author all the time.

That’s true. It was to some extent a result of the ‘factory model’ that Singer had set up in the COW project. He collaborated a lot with Melvin Small, a senior scholar, but he was out of the picture when I joined the project. Even Paul Diehl, one of the most successful students from the COW project, never co-authored with Singer. Mike Wallace did, but after he got his PhD. Diehl, by contrast, has published with his graduate students. So have I, extensively. And so have you! I regard partnerships with younger scholars as very productive. And I think most grad students do, too.

A South Asian Orientation

We’ve talked about your relationship with Korea. But you’ve also co-authored with several Indian scholars. How did that come about?

I have coauthored with an Indian historian, Kaushik Roy. We have written two books together, co-edited four volumes, and co-edited a special issue of a journal. He is an extraordinary scholar. We met after I gave a lecture at the Oslo Summer School. He came up to me and asked several insightful questions. He followed through via email and proposed a joint project. We applied for funding from the Norwegian Ministry of Defense and received the grant. Indeed, we have received two grants from the MoD. I have been interested in South Asia for a long time. Remember, I did my doctoral fieldwork in Pakistan. All of my books with Kaushik have been on South Asian politics (including Afghanistan). Our most recent book is Limited War in South Asia: From Decolonialization to Recent Times (Routledge).

I have also closely collaborated with Mansoob Murshed, an economist, who is of Bangladeshi background. We met at a World Bank conference that had been organized by Paul Collier. We hit it off from the beginning. I regard him as a good friend. We published a reasonably highly cited article on horizontal inequality in Nepal as it related to the civil war. We now have an article on food riots under review.

Scott with Anke Hoeffler and Paul Collier at a conference in Norway in January 2001. Collier was instrumental in moving the World Bank towards evidence-based research on conflict. His 2004 article with Hoeffler is one of the most frequently-cited articles on civil war. Photo: Private archives

Gauging the Future of Peace Research

Perhaps we can talk a little bit about the future of our discipline. Where do you see peace research and the study of conflict going in the future? You are not allowed to respond with a standard line that I often use when asked such questions: There was a jazz musician who said, ‘Man, if I knew where jazz was going, I’d be there already.’ But where do you think we are moving?

My answer today is somewhat different than it would have been 20 years ago. Then, I was very worried about a hyper-polarized environment with ‘critical theorists’ on one side and those with an extreme empirical orientation on the other. But strong critical theory, while it still exists in tiny pockets, never took over. It certainly doesn’t play a big role in peace science anymore, or even in peace studies. In recent years, I think people like Andy Mack with his Human Security Project played a profound role, as well as Paul Collier in moving institutions like the World Bank and the UN towards evidence-based research.

To go on with ontological debates about what we can or cannot know, doesn’t get us anywhere. Particularly if you want to try to solve real-world problems. If somebody can map out the situations and talk about the patterns and how they can be changed, we have some meat on the bones. As a practitioner, I would find this more valuable than endless discussions about the nature of science and knowledge.

Another important development is more and better recording of data, including information disaggregated in time and space. Just focusing on the nation, the state, and the year as the units of analysis is no longer good enough. You need to break it down to smaller units. Certain questions, like politics and governance, are obviously still going to be important at the nation-state level, although they also have local components. A lot of conflict analysis must look to the sub-national level, particularly in order to understand how resources affect conflict. As you yourself showed clearly in your work on diamonds and conflict. If you only look at the nation-state level, you would think that diamonds were fueling a conflict in Russia. But of course, the conflicts were mainly in the Caucasus and the diamonds were in Siberia, so they played no role whatsoever. This trend towards more disaggregated work has been going on for a few years now and will accelerate, I think.

Another new trend where I think we will see more work is to take advantage of research designs where we can better ascertain causal inference, such as quasi-experimental designs. In the next ten years I think we are going to see a lot more of these, or people doing natural experiments. For instance, a natural disaster occurs, and you use it as an interruption and then look at the differences before and after.

Finally, I think we will see a lot more use of data from social media. Right now, Twitter provides the most useful source of such data; indeed, techniques have been developed and are being developed that enable social scientists to better appreciate the relationship between social media use and protest activities. It may be easier to do this for non-violent protest than for violent. If you are starting an organized guerrilla movement or some other violent activity, you may want to keep it more secret.

To go back to your first point, I basically agree when you talk about the dominant position of peace science relative to the critical approaches. But there are also signs in the opposite direction. Take the decolonization movement. That actually originated within PRIO to some extent … Or the attack on Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver in Security Dialogue for practically being racists by citing ancient scholars.

A lot of people were already in the profession back when critical theory and critical perspectives were on the rise. The difference between those people, and our people so to speak, is that they are more like artists. So, your analogy with jazz I think is right. But what’s art and how do you become an artist? One of the worst critiques of an artist is that they are derivative. But for me as a scientist, if my theory is said to build on somebody else’s, it is the best compliment I can get! Implicitly, that means that it’s derivative. Our work is good if it is derivative, but for an artist it’s bad. For critical theorists, their perspective on peace studies is like art rather than science. There is no knowledge base to build on. But most policy makers really do believe there are facts, there really is a world out there, there is a way to understand things, and they can make the world better. It doesn’t fit the artist perspective. There will always be those artist types out there. They will continue to invent a new thing to cause some commotion about.

I should note though that some critical theory has provided on occasions useful insights and criticism. Jeff Checkel’s recent work is hated by some of the more radical critical theorists, but I think [Andrew] Bennett and Checkel’s work is excellent.

Unlike me, you haven’t lived through the time when critical theory and Marxism were ascendant in peace research, which in many ways tore peace research apart. Several institutions split and closed down because of this.

Oh, and Galtung basically turned his back on PRIO. But this didn’t happen in the nineties with rising critical theory. When I was an undergraduate in the late seventies, there was a rise in anthropology of economics, much more evidence based. In the US, anthropology departments combine human origins people, archaeologists, and social anthropologists. But for most social anthropologists there’s no room for any behavioralist approach. The problem for anthropology in the future, especially at the University of Oslo, is that they attract so few students. There is a real danger that they will close the anthropology department down because there’s no demand.

I also wanted to ask you a little bit about political science at the University of Oslo. Peace research was founded in Norway by Galtung and other sociologists. I studied sociology myself, I never studied political science. Which is a bit bizarre, since I eventually became a professor of political science…

Yeah, but you really are a political scientist!

…but now when I look at people being recruited to the political science department, it’s a very different story.

The comparativists were always a little bit more quantitative. I think some of that spilled over into international politics. The political science department at the University of Oslo was a stronghold for people who argued for publishing in Norwegian. It still has such people, but most of them are emerita now. Since I was hired in 2015, the balance is completely tipped. The influx of non-UiO doctorates who get a job at the University of Oslo changes the perspectives considerably, too. But even among those who get a UiO doctorate, such as Tore Wig, their experience and working abroad is so much greater. And of course, he was at PRIO for a while, too …

Final question about the future: You have an MA in political science and an MS in economics and you always have interacted a lot with economists. Do you see more economists becoming interested in conflict? More cooperation? More theory in peace science derived from economic models?

To a large extent yes, and I think that economics has changed a lot, too. It has become more empirical. Some parts of it always were. Macroeconomists were always empirical. But micro might not have been. The behavioral approach has really had a profound effect. Even the Nobel Prize has moved towards acknowledging that change, even though these Nobel prizes are generally conservative, with the prize awarded long after the work was done. In 2019, they rewarded some experimental work. On the whole, I think that economics has become more of a general social science-oriented discipline since I was a student in applied economics. A Todd Sandler today wouldn’t have to start in Wyoming, then go to Iowa State, and end up at University of Texas-Dallas. I think he would have been at a more prominent school, like Stergios Skaperdas and Michelle Garfinkel at the University of California, Irvine, two more examples of really good peace researchers who do the modeling and are also empirically oriented.

Well, I don’t know if we have left any gaping holes, but we’ll probably wake up in the middle of the night to think ‘why didn’t I say that?’. Thank you for an interesting conversation!

- Nils Petter Gleditsch has been associated with PRIO since 1964. He served as the editor of Journal of Peace Research (1977–78, 1983–2010) and – under Scott Gates’ leadership – as head of the working group on environmental factors at the Center for the Study of Civil War (2002–07).